30 May 2006

22 May 2006

the bastis

I ended up following Lila Bai (who you have already met in earlier posts and who you see above) and Bano Bi, one of the women who was knocked unconscious when the police attacked in Delhi, if you remember that story. From Alu Factory we crossed Union Carbide Road and entered a narrow lane through an area known as "Chola," which lies immediately to the east of the factory premises. After winding through there for a while, we eventually reached Atal Ayubh Nagar, which hugs the northern perimeter of the factory. I took the above photo in Atal Ayubh Nagar.

I ended up following Lila Bai (who you have already met in earlier posts and who you see above) and Bano Bi, one of the women who was knocked unconscious when the police attacked in Delhi, if you remember that story. From Alu Factory we crossed Union Carbide Road and entered a narrow lane through an area known as "Chola," which lies immediately to the east of the factory premises. After winding through there for a while, we eventually reached Atal Ayubh Nagar, which hugs the northern perimeter of the factory. I took the above photo in Atal Ayubh Nagar. As I might have explained before, the Bhopal disaster is not just a gas leak that happened in 1984, it is a continuing disaster that continues to kill many people each month. And it began before 1984, before the gas leak. I'm am talking about water contamination. In addition to solar evaporation ponds in which Union Carbide overtly dumped bulk amounts of different toxic wastes while the plant was in operation, there are tons of extremely toxic chemicals that were simply abandoned in the factory after the gas leak. The factory was never and has never been cleaned up. Except for theft of construction materials, it is almost exactly the way it was left almost 22 years ago. Some of the abandoned chemicals are in bottles and cans. Most are in large cloth sacks or loose on the floor or ground. Huge oozing pools of carbaryl (brandname Sevin) tar sit baking in the sun on the ground. And mercury, too -- you know how much we worry about incredibly tiny, trace amounts of mercury in air, water, or food in the U.S.? Well, here in Bhopal at the UC factory, there are visible puddles of mercury sitting on the ground, gleaming in the sun, happy to bounce around playfully for the children who have been known to make a game of it. Union Carbide's chemicals spread deep into the soil and groundwater years before the methyl isocyanate tank burst in 1984. There is no methyl isocyanate on the premises today, by the way. MIC is extremely volatile and unstable, which is why Union Carbide's haphazard way of dealing with it caused the deadly eruption. There are plenty of other chemicals left, though, with names full of phenyls, benzyls, cyanates, chloros and naphthols. With every monsoon season, the piles of these substances get soaked and renewed plumes flow through the ground water streams underneath the neighborhoods north of the factory. The water is absolute poison, and roughly two thirds of the patients here at the clinic are here because of drinking it.

As I might have explained before, the Bhopal disaster is not just a gas leak that happened in 1984, it is a continuing disaster that continues to kill many people each month. And it began before 1984, before the gas leak. I'm am talking about water contamination. In addition to solar evaporation ponds in which Union Carbide overtly dumped bulk amounts of different toxic wastes while the plant was in operation, there are tons of extremely toxic chemicals that were simply abandoned in the factory after the gas leak. The factory was never and has never been cleaned up. Except for theft of construction materials, it is almost exactly the way it was left almost 22 years ago. Some of the abandoned chemicals are in bottles and cans. Most are in large cloth sacks or loose on the floor or ground. Huge oozing pools of carbaryl (brandname Sevin) tar sit baking in the sun on the ground. And mercury, too -- you know how much we worry about incredibly tiny, trace amounts of mercury in air, water, or food in the U.S.? Well, here in Bhopal at the UC factory, there are visible puddles of mercury sitting on the ground, gleaming in the sun, happy to bounce around playfully for the children who have been known to make a game of it. Union Carbide's chemicals spread deep into the soil and groundwater years before the methyl isocyanate tank burst in 1984. There is no methyl isocyanate on the premises today, by the way. MIC is extremely volatile and unstable, which is why Union Carbide's haphazard way of dealing with it caused the deadly eruption. There are plenty of other chemicals left, though, with names full of phenyls, benzyls, cyanates, chloros and naphthols. With every monsoon season, the piles of these substances get soaked and renewed plumes flow through the ground water streams underneath the neighborhoods north of the factory. The water is absolute poison, and roughly two thirds of the patients here at the clinic are here because of drinking it. After years of fighting for it, the Bhopali activist network here got the local government to begin bringing in clean(er) water by truck, or at least to promise to do so. The black cylinder you see in the photo above is one of countless water tanks peppering the basti's. When the weather is good, the trucks usually show up. When it's not, they simply do not come, citing unpaved roads unfit for truck access. Even when everything goes perfectly, though, there is not enough tank water to go around to everybody.

After years of fighting for it, the Bhopali activist network here got the local government to begin bringing in clean(er) water by truck, or at least to promise to do so. The black cylinder you see in the photo above is one of countless water tanks peppering the basti's. When the weather is good, the trucks usually show up. When it's not, they simply do not come, citing unpaved roads unfit for truck access. Even when everything goes perfectly, though, there is not enough tank water to go around to everybody. In the end, people are forced to use the unsafe water. After the tank program began, pumps with water that tested as undrinkably poisonous were painted red. The paint is mostly chipped off in the pump above, but the words on the shaft warn people to stay away. It's hard to do that, though, when it's a 110 degrees and there are no alternatives.

In the end, people are forced to use the unsafe water. After the tank program began, pumps with water that tested as undrinkably poisonous were painted red. The paint is mostly chipped off in the pump above, but the words on the shaft warn people to stay away. It's hard to do that, though, when it's a 110 degrees and there are no alternatives. Atal Ayubh Nagar has some of the worst rates of medical problems caused by water contamination.

Atal Ayubh Nagar has some of the worst rates of medical problems caused by water contamination. This guy is pointing at the Union Carbide factory.

This guy is pointing at the Union Carbide factory. Here it is, from the northern perimeter. The structure on the left that is partly obscured by the tree is what is left of the methyl isocyanate gas unit.

Here it is, from the northern perimeter. The structure on the left that is partly obscured by the tree is what is left of the methyl isocyanate gas unit. This is Ramgopal, who you might remember from the padyatra. He and his family live in Atal Ayubh Nagar, directly adjacent to the factory premises. The above photo is from Ramgopal's tiny back yard. You can see one of the factory's structures through the trees and bushes.

This is Ramgopal, who you might remember from the padyatra. He and his family live in Atal Ayubh Nagar, directly adjacent to the factory premises. The above photo is from Ramgopal's tiny back yard. You can see one of the factory's structures through the trees and bushes. I walked beyond Ramgopal's space to get a closer look. As you can see, there is nothing to keep kids or anyone else from going in and out of the factory. There is a guard who would stop me (or any adults, especially foreigners) if he were to spot me, but I don't think they bother chasing children. There has even been a little arrangement between the kids and the guards whereby the guards allow kids to come in and dismantle parts of the factory, go and sell them as scrap metal or material for new construction, and then split the money with the guards.

I walked beyond Ramgopal's space to get a closer look. As you can see, there is nothing to keep kids or anyone else from going in and out of the factory. There is a guard who would stop me (or any adults, especially foreigners) if he were to spot me, but I don't think they bother chasing children. There has even been a little arrangement between the kids and the guards whereby the guards allow kids to come in and dismantle parts of the factory, go and sell them as scrap metal or material for new construction, and then split the money with the guards. And we're in. Within minutes of arriving at Ramgopal's house, Bano Bi had covered her mouth and nose with cloth and was saying something about there being a gas leak. I didn't think she was being serious, especially because I knew of no gas that could leak. There was unmistakably a heavy presence of something in the air, ever so slightly irritating in my noise and throat -- something similar to what you might smell downwind from a new floorwaxing job. I just wasn't convinced it was toxic gas from the factory. Lila Bai didn't seem too concerned, and I didn't want to leave before getting some photos and spending a little time at Ramgopal's house. After a while, though, Lila Bai seemed worried, too. They were saying that in the extreme heat the chemicals lying all over the ground are basically baked into producing harmful vapors that waft over and fill the bastis. Ramgopal and his family didn't seem worried at all, as you can see in the photo below. Ramgopal has lived there for 18 years. The effects of the poisons, whether from water or air, are visible on his skin. He does tailoring work from inside his home.

And we're in. Within minutes of arriving at Ramgopal's house, Bano Bi had covered her mouth and nose with cloth and was saying something about there being a gas leak. I didn't think she was being serious, especially because I knew of no gas that could leak. There was unmistakably a heavy presence of something in the air, ever so slightly irritating in my noise and throat -- something similar to what you might smell downwind from a new floorwaxing job. I just wasn't convinced it was toxic gas from the factory. Lila Bai didn't seem too concerned, and I didn't want to leave before getting some photos and spending a little time at Ramgopal's house. After a while, though, Lila Bai seemed worried, too. They were saying that in the extreme heat the chemicals lying all over the ground are basically baked into producing harmful vapors that waft over and fill the bastis. Ramgopal and his family didn't seem worried at all, as you can see in the photo below. Ramgopal has lived there for 18 years. The effects of the poisons, whether from water or air, are visible on his skin. He does tailoring work from inside his home. By the time I had clicked this photo Bano Bi was getting frantic, so I thanked everybody, said goodbye, and followed her out of there. I still don't know what the smell was or whether or not it was harmful, but the farther we got away from the factory, the less I smelled it. When I got back to Sambhavna I told people about it and Rachna said she smells it almost every time she goes to Atal Ayubh Nagar. No one is sure what it is.

By the time I had clicked this photo Bano Bi was getting frantic, so I thanked everybody, said goodbye, and followed her out of there. I still don't know what the smell was or whether or not it was harmful, but the farther we got away from the factory, the less I smelled it. When I got back to Sambhavna I told people about it and Rachna said she smells it almost every time she goes to Atal Ayubh Nagar. No one is sure what it is. Atal Ayubh Nagar with the MIC tank towering above it.

Atal Ayubh Nagar with the MIC tank towering above it. By this time we had run into Shehzadi, who not only walked all the way to Delhi, but did the hunger strike, too. She was excited to take me on a little tour of her neighborhood, Blue Moon Colony, which you see here beyond the railroad tracks. Blue Moon Colony is also severely affected by water contamination.

By this time we had run into Shehzadi, who not only walked all the way to Delhi, but did the hunger strike, too. She was excited to take me on a little tour of her neighborhood, Blue Moon Colony, which you see here beyond the railroad tracks. Blue Moon Colony is also severely affected by water contamination. After hanging out for a while at Shehzadi's, we went over to visit her sister, Nafeesa, who also came on the padyatra to Delhi.

After hanging out for a while at Shehzadi's, we went over to visit her sister, Nafeesa, who also came on the padyatra to Delhi. This is Nafeesa's son and her grandchildren.

This is Nafeesa's son and her grandchildren. Bano Bi, Lila Bai, Nafeesa, and Munni Bi (from left to right) pause to point out the factory in relation to the different bastis as we headed back across the railroad tracks to go to Bano Bi's neighborhood, Arif Nagar. Munni Bi was also on the padyatra. She lives near Nafeesa, north of the train tracks.

Bano Bi, Lila Bai, Nafeesa, and Munni Bi (from left to right) pause to point out the factory in relation to the different bastis as we headed back across the railroad tracks to go to Bano Bi's neighborhood, Arif Nagar. Munni Bi was also on the padyatra. She lives near Nafeesa, north of the train tracks. Bano Bi poses with her daughter-in-law and her grandchildren in part of their home.

Bano Bi poses with her daughter-in-law and her grandchildren in part of their home. Bano Bi's son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren in the doorway to their home as I say goodbye and Bano Bi leads me halfway to Berasia Road, from where I can find my way back on my own. It was starting to rain.

Bano Bi's son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren in the doorway to their home as I say goodbye and Bano Bi leads me halfway to Berasia Road, from where I can find my way back on my own. It was starting to rain.

18 May 2006

rain

Long ago -- what seems like years and years ago now -- I vaguely thought the monsoon was an unpleasant thing. I don't know why. It was just a intuitive assumption. I probably thought the word "monsoon" sounded scary. It does rhyme with "typhoon". I knew it had to do with torrential downpours, and naturally assumed it was something people dreaded.

Long ago -- what seems like years and years ago now -- I vaguely thought the monsoon was an unpleasant thing. I don't know why. It was just a intuitive assumption. I probably thought the word "monsoon" sounded scary. It does rhyme with "typhoon". I knew it had to do with torrential downpours, and naturally assumed it was something people dreaded.It is just the opposite. I didn't need to be told this explicitly. The deadly afternoon sun was happy to teach me. Just one typical day in May in Bhopal and you will understand within minutes that anything at all that interrupts the pain of that sun is cause for celebration. And if it involves getting drenched in cool water falling from above, that's even better. Beyond comfort, the monsoon is extremely important for agriculture and delays in its arrival cause much anguish among farmers in this part of the world.

Today it rained for the first time. The sky has been teasing us with strange winds and random drops of water for a few days now. This afternoon I was passing in and out of sleep in my bed when there suddenly came a wind so strong and loud it woke me up. There was deep, rolling thunder, too. And then suddenly the roof tiles became like drums. I bolted up and pulled back the mosquito net to run outside.

The water hit my face immediately -- it was being blown in sheets through the clinic. The air smelled like plant and dust. It was the most comfortable I have felt since arriving here three weeks ago. I looked out towards the clinic's garden to see one of the guards striding triumphantly through the downpour with both arms raised in the air, fingers pointing upwards like he had just made a touchdown. Very uncharacteristic for him. From the other side of the terrace I could watch the "street" (not the best word, but I don't know what else to call it), where rain-soaked, shrieking children were running up and down and twirling each other around while their more world weary parents made adjustments to roofs made of tin, wood, and sheet plastic weighted down by old tires.

For lack of anything better, the French girls and I celebrated with a shared packet of instant coffee and dry cookies from the "corner store" (again, not the best name for it, but it will have to do for now). This is not the monsoon. We don't think it is, at least. It's not supposed to come for another month. This is probably just a rogue caravan of storms. It's has already been raining every day in the Northeastern States (Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya, etc.), Bangladesh, and Kolkata (Calcutta).

There are also negative consequences to the monsoon, of course. Many hillside and mountain roads become dangerous or impassible because of landslides, and so many people die from flooding in certain places like Bangladesh that the whole world hears about it. Drinking water supplies are inevitably tainted by overflowing sewers and run-off, creating spikes in waterbourne diseases, cuts and scrapes don't heal very easily in the humid air and are more prone to infection, and it becomes almost impossible to dry any laundry. For now, though, all anyone can think about is how good it feels to watch the dark clouds go to battle with the sun and to feel their cool, wet victory run down our cheeks and our necks.

13 May 2006

Chambal

Lions to be set free to deal with bandits by Shaikh Azizur Rahman

THE WASHINGTON TIMES, August 27, 2005

CALCUTTA -- The government of a state in India has come up with a wild idea to control the menace of bandits who are becoming active again in the country's heartland. The government of Uttar Pradesh plans to unleash dozens of lions in the forested ravines to flush out the bandits from their hide-outs.

The 14,400 square-mile Chambal Valley region -- with its maze of undulating ravines and dense forests, spread across the states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh -- has been controlled by ruthless forest brigands, locally known as "dacoits," for decades. The gangs these days mostly abduct people for ransom and have been charged in more than 4,000 kidnappings and 180 killings in the two states in the last five years. The government of Uttar Pradesh plans to let loose 25 lions in the valley, to entertain wildlife lovers as well as to scare away the dacoits. The lions, from a national park in the western state of Gujarat, will be released in the forests of Etawah in northern Chambal Valley. "Apparently, the animals are meant for a lion safari park in the forest. But the presence of such large carnivores in the vicinity will be frightening for the dacoits," a forest ranger in Etawah said. "They were never afraid of hyenas and wolves of the Chambal ravines. But lions will scare them away this time, we are sure."

The project has been welcomed by Uttar Pradesh police. If it succeeds in Uttar Pradesh, the state will press Madhya Pradesh to extend the lion safari into that state as well, said S.K. Chaudhary, the top police officer in Etawah. "If no technical hurdle crops up suddenly, by the middle of next year Chambal ravines will see the lions," Mohammad Ahsan, the wildlife chief of Uttar Pradesh said in a television interview. Guddu Khan, a 32-year-old Etawah businessman who was kidnapped by a Chambal gang for three months five years ago and was released after paying a ransom of $16,250, doubts the lions would be able to deter the dacoits. "[The dacoits] are very good hunters as well. They will shoot down the lions the way they killed many leopards, wolves and other wild animals in the area," he said.

Most of Chambal Valley is inaccessible by police cars and jeeps. About 25 gangs with more than 300 members still operate in the two states and, in spite of chasing them regularly, police have failed to kill or capture most of them. Chambal ravines were the haunt of famous "Bandit Queen" Phoolan Devi, whose story of rape and revenge was made into a film in the 1990s. After spending 11 years in jail, she joined politics and became a member of Parliament -- before being killed in 2001. Nirbhay Singh Gujjar, 55, who controls a large part of the ravines, is now considered the Bandit King of Chambal. Gujjar, wanted in more than 50 killings and 280 kidnappings, has a reward of $5,750 on his head. Seema Parihar, another female bandit, portrayed herself in a recent Bollywood film on her life. The Indian government refused her application for a passport to attend a premiere of the film in Britain this week.

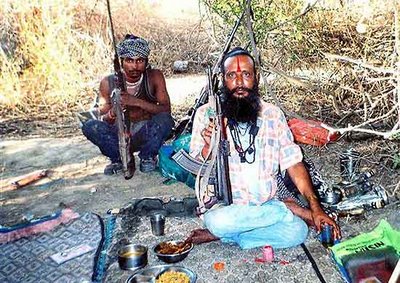

Note from Michael: Nirbhay Singh Gujjar has since been killed in a gun battle with police, not too long ago. Here are a couple of photos (*not* my photos - top is AP, bottom is Telegraph of India) of Gujjar from when he was still alive and afterwards:

Below is Phoolan Devi, who developed quite a cult following all over the world for what is at least the legend -- that as a very poor girl she was raped by upper caste members (very common and unpunished crime) and after some time returned to that town as the head of a dacoit gang to successfully massacre the upper caste men there. She later ended up becoming a local politician, but was assassinated a few years ago.

***********************************************************************

Here are a few photos I took in the area:

Sathyu (in purple kurta, of course) talks to a roadside well-wisher just a few kilometers from the Chambal River.

This is the way the land is in the Chambal area. You can see immediately why it is inconquerable by any other than those who spend their whole lives winding through its ravines, learning every detail of its contours. Law enforcement or any other other structured organization has no chance in navigating this kind of a playing field. You could be literally 30 feet from the people you were looking for and be unable to see them over the narrow ridges and humps of land that formed an uninterrupted labyrinth for far as I could see.

As we approached the region, the highway that had become very wide and modernized after we passed through Gwalior in northern Madhya Pradesh, suddenly tapered and in no more than 50 feet went from being a divided, smoothly paved, railed highway to being just a notch above a dirt road. The change was so abrupt I felt compelled to turn around and take a photo (immediately below). We were in.

We passed through a small village very close to the Chambal River. A few padyatris to the opportunity to go ask the people in the above photo for some water.

We passed through a small village very close to the Chambal River. A few padyatris to the opportunity to go ask the people in the above photo for some water.

Nafeesa, Jagarnath Das, and Ramkishin stride confidently across the dilapidated bridge that stretches high above the Chambal.

Nafeesa, Jagarnath Das, and Ramkishin stride confidently across the dilapidated bridge that stretches high above the Chambal.

Some ancient fort that has virtually zero hope of being visited any time soon. Lonely Planet certainly makes no mention of this part of India. This is a little tongue of Rajasthan that is wedged between Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

Some ancient fort that has virtually zero hope of being visited any time soon. Lonely Planet certainly makes no mention of this part of India. This is a little tongue of Rajasthan that is wedged between Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. The padyatra is temporarily mixed in with a long string of women and children carrying head loads down the road.

The padyatra is temporarily mixed in with a long string of women and children carrying head loads down the road.

12 May 2006

a walk in Bhopal

It is about a five minute walk from Sambhavna to the Union Carbide factory. It is so hot at noon (when I took this photo) that the streets become very still and empty.

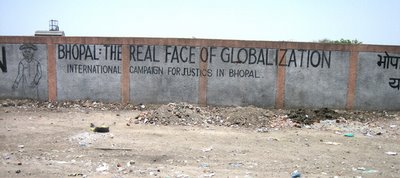

It is about a five minute walk from Sambhavna to the Union Carbide factory. It is so hot at noon (when I took this photo) that the streets become very still and empty. This is the wall of the factory of the front (entry) side of the factory. Because of the factory's huge size, the perimeter wall is quite long and is almost completely covered with graffiti about the continuing disaster.

This is the wall of the factory of the front (entry) side of the factory. Because of the factory's huge size, the perimeter wall is quite long and is almost completely covered with graffiti about the continuing disaster.

Amanta Bi (left) and Guddi Bi (right) looking quite happy at Alu Factory when I arrived. Both women walked all the way to Delhi on the padyatra. Amanta Bi is always smiling and loves having her picture taken.

Amanta Bi (left) and Guddi Bi (right) looking quite happy at Alu Factory when I arrived. Both women walked all the way to Delhi on the padyatra. Amanta Bi is always smiling and loves having her picture taken.

This is Ramgopal. He was also on the padyatra. Ramgopal lives north of the factory and is severely affected by water contamination. Like so many people around here, he has a hard time working enough to support himself and his family.

This is Ramgopal. He was also on the padyatra. Ramgopal lives north of the factory and is severely affected by water contamination. Like so many people around here, he has a hard time working enough to support himself and his family.

Narayan Singh addresses the meeting. About half the people in this photo were on the padyatra -- Mulchand in white, Ramgopal in blue, Chhote Khan in dark brown, Jabar Khan in fuscia, Shanta Bai, the woman in white and pink, and Nawal Singh in white, sitting in the background.

Narayan Singh addresses the meeting. About half the people in this photo were on the padyatra -- Mulchand in white, Ramgopal in blue, Chhote Khan in dark brown, Jabar Khan in fuscia, Shanta Bai, the woman in white and pink, and Nawal Singh in white, sitting in the background.

Irfan Bhai talking to Mira and a woman whose name I can't remember. Behind him, written on the wall, is the long standing invitation announcement that every Wednesday from 12 to 2 in the afternoon is a meeting here. Alu Factory is defunct. "Alu" means "potato". I think they used to make potato chips and stuff like that here.

Irfan Bhai talking to Mira and a woman whose name I can't remember. Behind him, written on the wall, is the long standing invitation announcement that every Wednesday from 12 to 2 in the afternoon is a meeting here. Alu Factory is defunct. "Alu" means "potato". I think they used to make potato chips and stuff like that here.

I'm just posting this one because of cuteness. This is Nawal Singh's baby grandchild, patiently waiting for the meeting to be over.

I'm just posting this one because of cuteness. This is Nawal Singh's baby grandchild, patiently waiting for the meeting to be over.

In this photo you can see the methyl isocyanate tank tower in the upper left.

In this photo you can see the methyl isocyanate tank tower in the upper left.

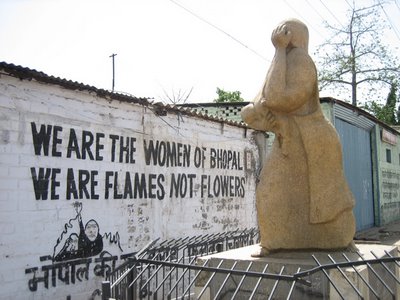

This statue, across the street from the Union Carbide factory, is the only memorial that exists in Bhopal. It has been here since shortly after the leak -- I'm pretty sure it was erected within a year or two. It, too, is used as a meeting spot for direct actions here. "we are flames not flowers" is a very popular slogan for Bhopali activists in Hindi, below -- "phul nahin, chingaari hain!" The grassroots response to the leak and continuing injustice here has had some very interesting side effects I haven't talked much about yet here. One has been the unification of involved Hindus in Muslims to a level that is very unusual for India, and another has been the empowerment of women, especially Muslim women. Muslim women have felt encouraged to take off their veils and burkas in meetings and many have ended up discarding them altogether. The disaster also created thousands of widows, who then banded together to form new groups essentially based around exercising their power as women, to survive. It's not all some romantic, pretty picture, of course. It's been an awful 21 years, and many widows were stuffed into squalid "widow's colonies" where they were eventually forced into prostitution to survive.

This statue, across the street from the Union Carbide factory, is the only memorial that exists in Bhopal. It has been here since shortly after the leak -- I'm pretty sure it was erected within a year or two. It, too, is used as a meeting spot for direct actions here. "we are flames not flowers" is a very popular slogan for Bhopali activists in Hindi, below -- "phul nahin, chingaari hain!" The grassroots response to the leak and continuing injustice here has had some very interesting side effects I haven't talked much about yet here. One has been the unification of involved Hindus in Muslims to a level that is very unusual for India, and another has been the empowerment of women, especially Muslim women. Muslim women have felt encouraged to take off their veils and burkas in meetings and many have ended up discarding them altogether. The disaster also created thousands of widows, who then banded together to form new groups essentially based around exercising their power as women, to survive. It's not all some romantic, pretty picture, of course. It's been an awful 21 years, and many widows were stuffed into squalid "widow's colonies" where they were eventually forced into prostitution to survive.

The graffiti above addresses Dow Chemical, Union Carbide's new owner. The guy in the photo is Ashphak, one of my favorite people here. Ashphak was on the padyatra and was one of my main companions, looking out for me and helping me with the difficult task of keeping my laptop safe and out of the extreme daytime heat. I don't know what to say about Ashphak - he's just pure kindness, to an extent that is almost jarring for someone coming over here from the States.

The graffiti above addresses Dow Chemical, Union Carbide's new owner. The guy in the photo is Ashphak, one of my favorite people here. Ashphak was on the padyatra and was one of my main companions, looking out for me and helping me with the difficult task of keeping my laptop safe and out of the extreme daytime heat. I don't know what to say about Ashphak - he's just pure kindness, to an extent that is almost jarring for someone coming over here from the States.